Page 4 End

Taccha-Sukara-Jataka

The Carpenter’s Boar

Picture by: PongPang

Coloured by: Mint, PongPang

End

The Origin of the Story

Taccha-Sukara-Jataka

This story the Lord Buddha told while dwelling at the monastery of Jetavana. In that occasion, Bhikkhus were socializing with each other in the Dhamma hall enthusing about King Pasenadi’s victory in the battle with Ajātasattu, which came as following the direction of the Elder Dhanuggaha-tissa battle strategic comments.

The Lord arrived at the gathering place, learning about the topic of the conversation from the Bhikkhus thus said He, Behold monks, not only now but also in the former time that the Elder Dhanuggaha-tissa employed his military savvy in strategizing a clever battle operation; hence the Lord revealed the story as follow:

Once upon a time, King Brahmadatta reigned the kingdom of Banares. The Bodhisattava was born a tree sprite in the woods. In a carpenter’s village close to the city gate of Banares lived a carpenter who went into the forest to cut wood. He found a young fallen boar in a pit, which he brought home and reared. The boar grew up to be a loveable burly beast with two beautiful tusks and was named Taccha-sūkara meaning carpenter’s boar.

The boar became his servant doing the tasks such as: trees he turned over with his snout and brought to him: he hitched the measuring line around his tusk and pulled it along, fetched and carried adze, chisel, and mallet in his teeth. The carpenter, who loved Taccha-sūkara as his own son, and feared lest someone might do him a mischief there, let him go free in the forest. The boar wandered, searching far and wide the woods and hills around till found a place of lovely hills and pleasant rills with abundant roots and fruits and plenteous store of food, there living a herd of boars. Upon spotting Taccha-sūkara, the boars came to him

Taccha-sūkara told them that he had wandered, searching for his kin and lo, his kin were found. Here he would dwell with all his kin, not anxious, at his ease, having no trouble, fearing nothing from any enemies. On hearing, the boars responded that even though it was a truly pleasant living place, a foe was here! Taccha-sūkara said it was anticipatory as I saw their bodies lost their strength, having no tusks to show in spite of dwelling that such a plenteous place. Who was that foe? The boars said a king of beasts, early in the morning came and took one boar spotted with teeth to bite. Taccha-sūkara asked if the tiger came every day. The boars said, yes. How many they were, he asked. The boars said only one. There are hundreds in number among you, said Taccha-sūkara, why couldn’t you destroy only one enemy? The boars said they could not. Taccha-sūkara told the boars they could catch the tiger if they worked together. Where was him? At the mountain over there, said the boars.

The carpenter’s boar now having made the boars all of one mind searched about for a place and made them take food while it was yet night; then very early in the morning, he explained to them how the order of battle was of three kinds:

1. Waggon Battle

2. Wheel Battle

3. Lotus Battle.

He knew the place of advantage to take, so that victory might be won. After which he decided to employ the Lotus Battle to fight the tiger, which arranged in this manner.

In the midst, he placed the sucking pigs and around them their mothers,

Next to these the barren sows,

Next a circle of young porkers,

Next the young ones with tusks just a budding,

Next the big tuskers and the old boars outside all. Then he posted smaller squads of ten, twenty, thirty apiece here and there. He made them dig a pit for himself and for the tiger to fall into a hole of the shape of a winnowing basket; between the two holes was left a spit of ground for himself to stand on.

Then he with the 60-70 stout fighting boars went around everywhere encouraging the boars who were preparing for the battle. As he was thus engaged the sun rose. The tiger woke up and thought it was about time to go out for food. He, coming forth from place, appeared upon the hill top. The boars looked at the tiger and looked at each other’s eye. Taccha-sūkara signaled to them to do whatever the tiger did: the tiger gave himself a shake and as though about to depart, made water; the boars did the same. The tiger looked at the boars and roared a great roar; they did the same.

Observing what the boars were at, the tiger thought they had changed somehow; today they face him out as enemies, in orderly bands: some warrior had been mustering them; it might be his defeating day thus he must not go near them today.

In fear of death he turned tail and fled to his place.

Near the tiger’s habitat was the hermitage of a sham ascetic waiting to feast on the boar brought back by the tiger, seeing the tiger empty-handed, the ascetic asked,

Behold tiger, every day you wander around to abjure killing of the boar. Today, you come back, I can see your teeth no longer bite, your strength exhausted quite.

In response, the tiger said once those boars would hurry-scurry all about upon seeing me within sight. But now, brother by brother all together stood, invincible, faced me out. All agreed they might hurt me.

The ascetic wanted to hearten the tiger thus he said: Royal tiger, you know not your own power. Go back to those boars, making one roar only and a spring —there will not be two of them left together, I dare swear! Having heard the sham ascetic’s encouragement, the tiger plucked up the courage to return to the herd of boars. The boars told carpenter's boar that the tiger was come again. Taccha-sūkara was taking his stand upon the ridge between the two pits. ‘Fear not,’ said he, comforting the boars, ‘We will catch him.’

The tiger after having made a loud roar with all speed sprang towards the boar, but the boar rolled tail over snout in the first hole. The tiger could not check his onset and fell all of a heap into the pit shaped like to a winnowing fan. Up jumped the boar in a trice, buried his tusks in the tiger's thigh, pierced him to the heart, devoured the flesh, bit at him, bundled him over into the further pit, crying, ‘There, take the varlet!’ They who came first got one chance apiece of nuzzling a mouthful, those who came later went about asking, ‘How does tiger’s meat taste?’

Taccha-sūkara came out of the pit and looking round upon the others, said, ‘Well, don't you like it?’ But they answered, ‘My lord, you have done for the tiger and that’s one; but there is another left worse than ten tigers.’ ‘Who is that, pray?’ ‘A sham ascetic, who eats the meat which the tiger brings him from time to time.’ ‘Even the tiger could be done, the ascetic is no big deal. Come along then, and we will catch him.’ So they quickly sprang off together. Now the sham ascetic was watching the road and expecting the tiger to come every minute. And what should he see coming but the boars! ‘They have killed the tiger, methinks, and now they are come to kill me!’ Away he ran, seeing the boars were chasing after him, leaving all his personal belongings on the ground and climbed up a wild fig tree.

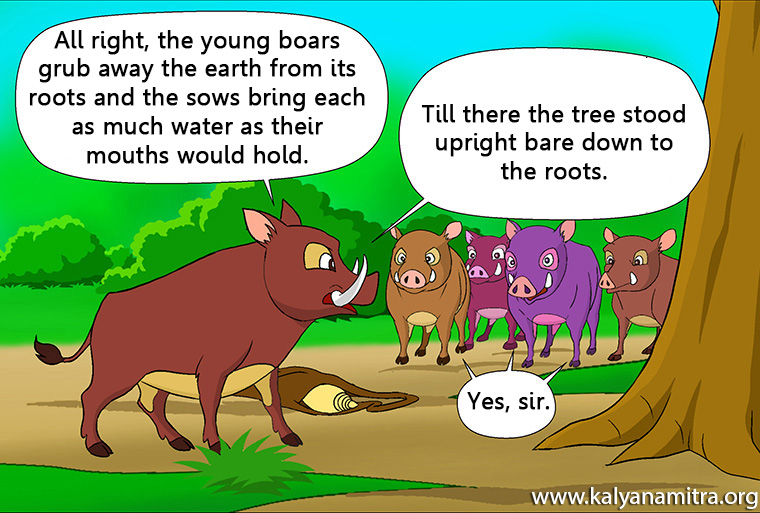

‘He has climbed a tree.’ said the boars to their leader. ‘What tree?’ ‘A fig tree.’ ‘All right, we shall have him directly.’ Taccha-sūkara made the young boars grub away the earth from its roots, and the sows bring each as much water as their mouths would hold till there the tree stood upright bare down to the roots. Then he sent the others out of the way, and going down on his knees, struck at the roots with his tusk: clean through the root he cut, as with an axe, down came the tree, but the ascetic never got as far as the ground, he was torn to pieces and eaten on the way.

Then the boars proposed to sprinkle Taccha-sūkara for their king. Water was fetched. Espying the shell which the sham ascetic used for his drinking, which was a precious conch with the spiral turned right wise, they filled it with water and consecrated carpenter’s boar there on the root of the fig tree; there the water of consecration was poured upon him. A young sow they made his consort.

Hence arose the custom which still prevails that in consecrating a king they seat

him upon a chair of fig wood and sprinkle him from a conch with spirals that run to the right.

Observing this marvel, the tree spirit sang their praise:

United friends, like forest trees —it is a pleasant sight, the boars united, at one charge the tiger killed outright.

When the Lord Buddha had ended this discourse, with these words, he identified the birth: ‘At that time Devadatta was the sham ascetic, Dhanuggaha-tissa was carpenter's boar and I myself was the tree sprite.’

The End